What is inflation?

Home › Finance glossary › Inflation

Living costs: Inflation is the increase in the cost of living due to a price rise for goods and services

Supply and demand: Inflation is generally affected by the supply and demand of goods or services. If supply is high, it typically follows that goods will cost less

UK inflation: The Bank of England’s inflation target is 2%, although recent global events have pushed the current UK inflation rate much higher than this

The information provided here is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. Please consult with a licensed financial adviser or professional before making any financial decisions. Your financial situation is unique, and the information provided may not be suitable for your specific circumstances. We are not liable for any financial decisions or actions you take based on this information.

What is inflation?

Inflation is a quantitative measurement of the rate at which the price of goods and services rises or the purchasing power of a currency falls. By definition, inflation is the increase in the cost of living due to increases in the prices of goods and services.

The inflation rate is a percentage used to determine the increase or decrease of prices during a specified period, typically up to a year. The inflation rate helps you decipher how quickly prices rose during a specific period.

How does inflation work?

Inflation is affected by the supply and demand for goods and services. In an open market where the demand for a product is great, the price for that product might also increase as supply diminishes due to people purchasing. By contrast, if the supply is greater than the demand, then the prices of the goods or services may decrease, tempting people into buying them.

What causes inflation?

The most common cause of inflation is what’s known as ‘demand-pull’ inflation, which happens when the demand for goods or services is higher than the supply. As people want to purchase a specific type of product, they are willing to pay a higher price.

‘Cost-push’ is another cause of inflation, which happens when supply is short but the demand is not, although it’s less common. For example, if a natural disaster damages gas supply lines, there could be a shortage in the gas supply, but demand wouldn’t change.

Another cause of inflation is money supply, which happens when a government prints too much money, resulting in too much capital for the volume of goods available and creating either demand-pull or cost-push inflation.

The final cause of inflation is called ‘built-in inflation’, which happens when people expect wages to increase as the price of goods increases. However, higher wages mean the cost of production also increases, and this, in turn, raises the price of goods and services again. Built-in inflation creates a continuous cycle that can greatly affect the economy.

How is inflation managed?

Central banks usually manage inflation by using monetary policy to try and avoid it increasing too much. Monetary policy is an action that a country’s central bank can take to influence how much money is in the economy, and how much it costs to borrow. For example, the Bank of England is targeting a UK inflation rate of 2% over a year.

A central bank can agree to increase the inflation rate over 2% in a bid to help improve the employment rate. If they do this, they will usually try and get back to the 2% inflation rate as quickly as possible, while allowing the rate to increase over a set period, especially if it has been low for a while.

What is the Consumer Price Index (CPI)?

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the measurement of the inflation of consumer prices in the United Kingdom. It measures the average price of food, transport and healthcare. The CPI is calculated by averaging out the price change of each item from a predetermined list of goods and services, and is used in calculating the rate of inflation.

What is the current rate of inflation in the UK?

The current rate of inflation in the UK can be checked on the Bank of England’s website.

This chart shows the UK’s historic inflation rates:

The different types of inflation indexes explained

As we’ve seen, there are two main types of inflation; demand-pull and cost-push. Demand-pull inflation is when there is more demand for goods and services than there is supply, causing an increase in prices, due to the shortage of goods.

Cost-push inflation is when the cost of creating or making the goods increases, and gives companies no choice but to increase their prices. For example, if the price of oil increases, a company that uses oil in their manufacturing processes may also increase the price of their goods, to make up for the oil price increase.

Aside from these two types of inflation indexes, there are other types of inflation to know about, which are:

Disinflation – when the rate of inflation falls, but prices are still rising in small amounts

Deflation – the direct opposite of inflation, deflation happens when the rate of inflation drops below 0%, making goods and services cheaper. Although this may sound like a good thing, it may have other effects on the economy. One such effect is that people spend less because the value of money is high. Deflation generally encourages people to save rather than spend

Stagflation – this happens when there is no economic growth and unemployment is rising with inflation. This means people’s wages fall, even as the price of goods and services rises

Reflation – this signifies the start of an inflation cycle after a recession has occurred. It can refer to a growing economy in conjunction with rising prices of goods and services.

What are the pros and cons of inflation?

Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

Consistently sitting at the target 2% inflation rate can be positive, because deflation is potentially damaging to the economy and can lower consumer spending and low growth. | High inflation rates can cause uncertainty and confusion, leading to fewer investments. |

Moderate inflation reduces the value of debt. | High inflation rates can lower international competitiveness, which can lead to fewer exports. |

Moderate inflation rates can allow prices to adjust and goods to sell at their original price. | Inflation can cause stagnant wage growth, which can lead to a decrease in income. |

A moderate range of inflation is a good sign of a healthy economy. | Inflation may decrease the value of savings, which particularly impacts elderly or retired people living on their savings. |

Moderate inflation rates allow wages to adjust. | Inflation can reduce government bonds’ real value, which can lead to investors demanding higher yields as compensation. |

If inflation is high, central banks may need to pursue a monetary policy, which means they will need to lower demand. In worst-case scenarios, this can lead to a recession. |

How do I beat inflation?

Stocks often beat inflation over the long-term, because companies can increase their share price to keep up with the rising costs brought about by inflation.

For example, if wages and production costs increase because of inflation, a company could pass on these costs to their consumers by raising their share prices, and the cost of their goods or service.

At Raisin UK, our marketplace is home to savings accounts with high interest rates from a range of partner banks, including savings accounts with inflation-beating rates*. Our fixed rate bonds tend to offer the most competitive rates of all account types, making them an ideal choice for long-term savings goals.

However, if you prefer to have a degree of flexibility, notice accounts may be a better option. They require you to give a short notice period to withdraw money, typically between 30 and 90 days, but offer more competitive rates of interest than easy access savings accounts.

Apply for a Raisin UK Account today

It’s free to register for a Raisin UK Account, and you can apply for any savings account in our marketplace for free in a few clicks, so why not see how you could grow your savings?

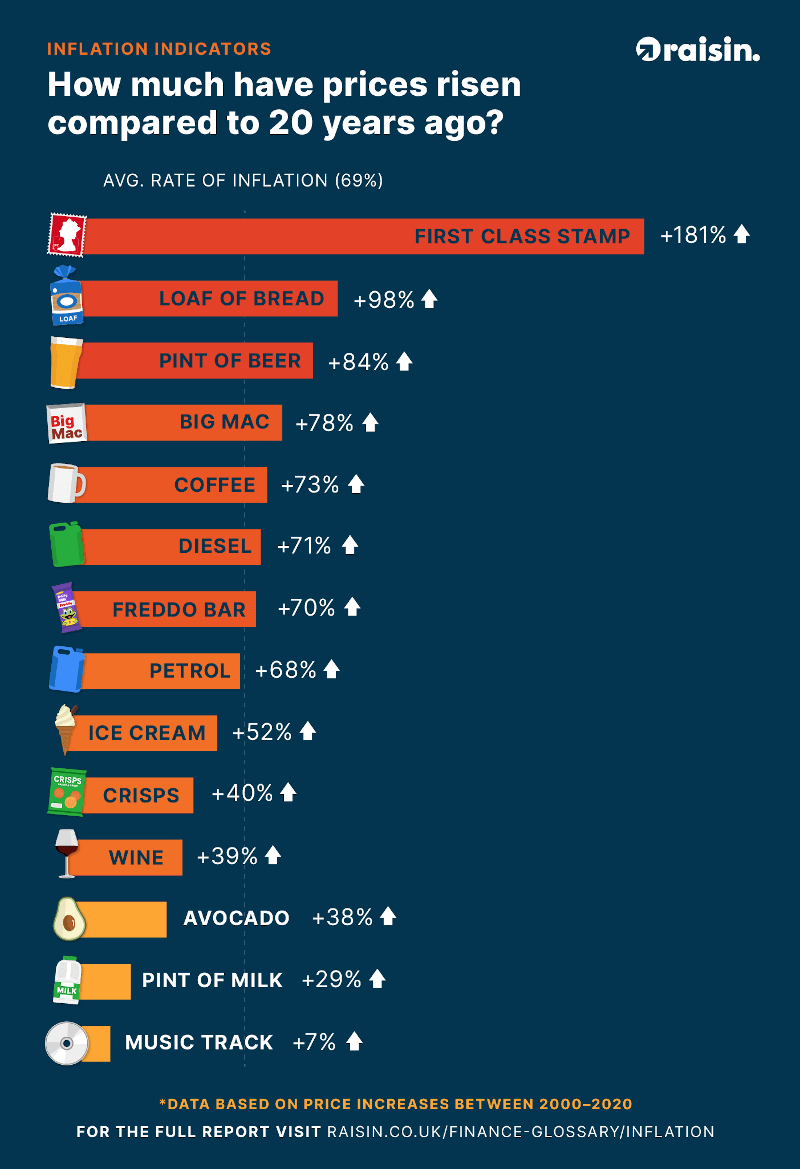

Inflation nation - how the price of everyday items has increased between 2000-2020

As the years go by, it’s not uncommon to see the prices of our favourite products rise to meet inflation. Over the past twenty years, inflation in the UK has risen by 69.43% according to ONS data. But just how many of our favourite products have risen above, inline or below the rising cost on average in the UK?

Is there anything more British than remarking on the price of a Freddo? Our research has revealed that the frog-shaped chocolate bar has increased in cost by 70% since the year 2000, and while it will still on average only set you back 17p, that’s enough to earn the wrath of any snacking shopper.

But it’s not just the infamous amphibian that’s putting more pressure on people’s pockets. We look at how the cost of everyday items has increased over the past 20 years, showing how inflation is impacting our outgoings and – in some cases – even saving us money.

Our table shows how much inflation is costing us for everyday items

Product | Price in 2000 | Price in 2020 | % Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

Stamps (First Class) | £0.27 | £0.76 | 181% |

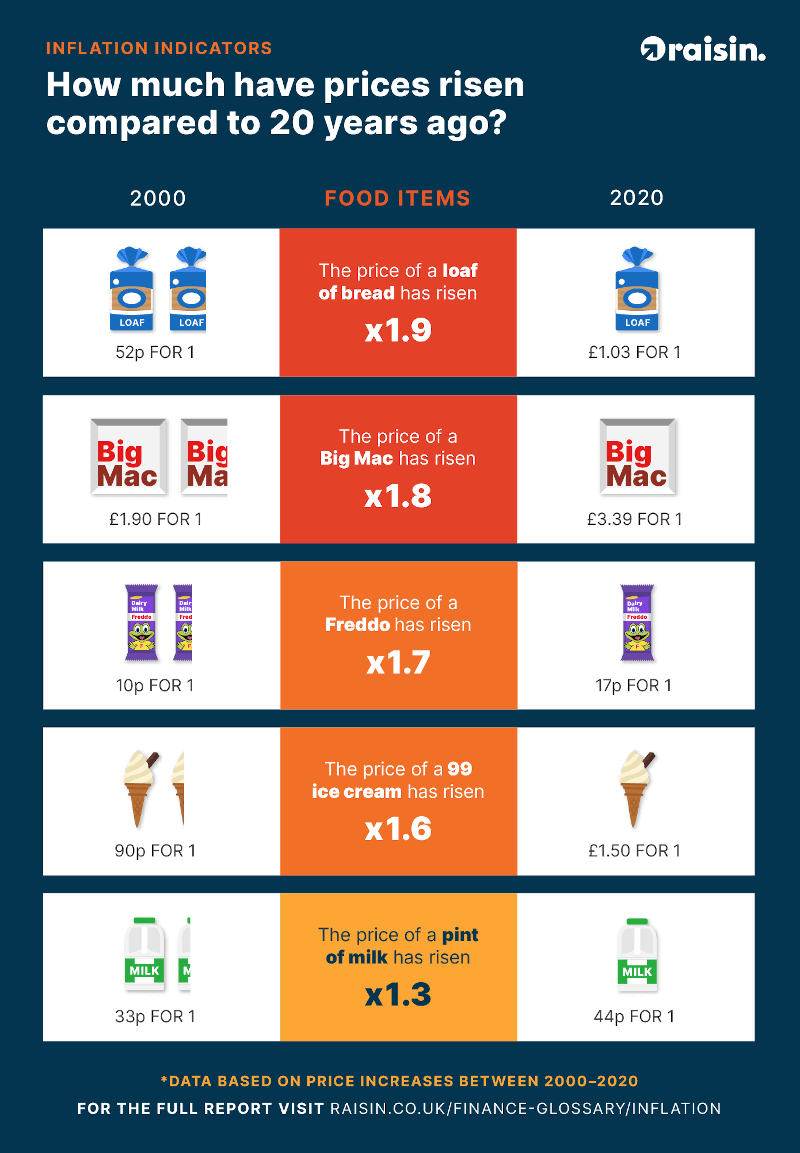

Loaf of bread | £0.52 | £1.03 | 98% |

Pint of beer | £1.90 | £3.49 | 84% |

Big Mac | £1.90 | £3.39 | 78% |

Takeaway coffee | £1.50 | £2.60 | 73% |

Diesel | £0.77 | £1.32 | 71% |

Freddo | £0.10 | £0.17 | 70% |

Petrol | £0.75 | £1.26 | 68% |

99 ice cream | £0.99 | £1.50 | 52% |

Packet of crisps | £0.30 | £0.42 | 40% |

Wine (175ml) | £2.90 | £4.02 | 39% |

Avocado | £0.72 | £0.99 | 38% |

Pint of milk | £0.34 | £0.44 | 29% |

Music | £0.91 | £0.97 | 7% |

A loaf of bread will cost 98% more dough

Another high flyer for inflation is a loaf of bread. At the turn of the millennium, a loaf of white, sliced bread would only cost you 52p, but 20 years later and the price has gone up to £1.03.

Bread isn’t the only food to cost more to chow down on. The price of a Big Mac, once a tasty bargain at £1.09, will now cost fast food feasters £3.39 – a whopping 78% increase. A packet of crisps has also seen a 40% rise (from 30p to 42p), while a 99 ice cream doesn’t – as the name suggests – only cost 99p. That price disappeared in 2000, with the 2020 price now a whole £1.50. Meanwhile, the demand for avocados has also impacted their price. A 38% increase has seen their cost shoot up from 72p to 99p, showing how changing tastes have brought about higher price margins.

How much for a pint of milk?

At the other end of the inflation scale, milk has only seen a 29% increase. In 2000, you’d have had to pay 34p to take home a pint, while 20 years later the price has gone up to 44p. Pints of another kind, however, have fared far worse. In a pub two decades ago, you could have a big night out for under £20, with a pint of beer only costing you £1.90. The UK average has shot up since then, with pubs charging you £3.49 for their standard serving. Savings can’t be found anywhere else on the menu either. A 175ml glass of wine would have cost you £2.90 in the year 2000, but anyone looking for a drink now would have to hand over £4.02 – a 39% increase.

The price of fuel is now 71% higher than in the year 2000

Filling up your car costs motorists thousands of pounds throughout the year, and the cost of getting from A to B is showing no signs of getting cheaper. A litre of diesel was only 77p 20 years ago, while it now costs drivers £1.32 at the pumps. Petrol, meanwhile, is close behind. A 68% increase has seen the price per litre go up from 75p to £1.26.

What about the products beating inflation?

It’s not all doom and gloom for highstreet shoppers. Some things have actually decreased in price since the millennium started, either due to a fall in popularity or a more competitive marketplace. Clothing has seen an average decrease of 38%, with online retailers forcing high-street stores to lower their prices to draw people in. Camera equipment has also seen a dramatic cost reduction. The rise of smartphones and their recording abilities has seen the demand for audio-visual devices plummet, with prices falling on average by 78%.

Can savings accounts beat inflation?

Yes, savings accounts can help in ensuring the money you save doesn’t drop in value against inflation, certainly more so than if you kept your money in a current account or as cash in your home. By depositing your money in a savings account with a rate better than the rate of inflation, your money will become worth more over time. Savings accounts rates have always fluctuated, but at Raisin UK, you’ll find savings accounts featuring competitive rates, some of which beat inflation*.

Footwear has gone down by 32%, while second-hand cars (38%) and financial service items (32%) have also seen prices go against the flow of inflation.

Methodology Inflation

Using data from the ONS Consumer price inflation time series and available information on historical prices, we’ve calculated the percentage increase in the price of these products from 2000 to 2020. Measured against the UK’s inflation rate (which has increased by 69.43%), we can determine if products are rising faster or slower than the average rate of inflation.

* At the time of publication (December 2020), the rate of inflation in the UK according to the ONS was 0.9% and the Raisin UK savings marketplace featured savings accounts with rates that exceeded this amount.